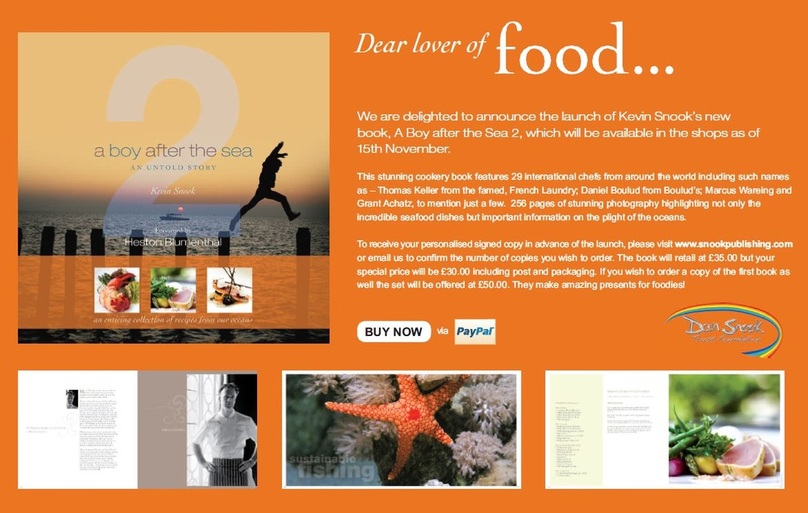

In the first book, a boy after the sea: an untold story, Kevin Snook presented us with a book that satisfies on every level, so much so that it won the 'Best in the World' for the fish and seafood category at the 2010 Gourmand World Cookbook Awards. But behind the recipes and the stunning photography, the book has a more serious and soul wrenchingly sad origin, Kevin Snook lost his 19 year old son Dan as a consequence of sexual abuse and drug addiction. Determined to honour his memory while at the same time helping others experiencing pain and suffering, Kevin set up The Dan Snook Trust Foundation which aims to help troubled people between the age of 15 - 25 years who have been subject to sexual or substance abuse. The full proceeds of both the first and the second book go to support the foundation.

The book itself reads like a Who's Who of cooking with the foreward written by Heston Blumenthal who is the Honary Vice Chairman of the charity. Later in the book, Heston shares his recipe for his famous Sounds of the Sea dish that is served daily at The Fat Duck restaurant in Bray. Meanwhile, Bray neighbour Alain Roux of The Waterside Inn details a recipe for quenelles of pike. In total, twenty six chefs share recipes across over 200 pages of the first book making it a very special cookbook indeed. Separating each of the 'chef sections', there is an array of beautiful black and white pictures celebrating our oceans, rivers and life contained therein and short discussion pieces on the role and ambition of The Foundation.

The book itself reads like a Who's Who of cooking with the foreward written by Heston Blumenthal who is the Honary Vice Chairman of the charity. Later in the book, Heston shares his recipe for his famous Sounds of the Sea dish that is served daily at The Fat Duck restaurant in Bray. Meanwhile, Bray neighbour Alain Roux of The Waterside Inn details a recipe for quenelles of pike. In total, twenty six chefs share recipes across over 200 pages of the first book making it a very special cookbook indeed. Separating each of the 'chef sections', there is an array of beautiful black and white pictures celebrating our oceans, rivers and life contained therein and short discussion pieces on the role and ambition of The Foundation.

a boy after the sea 2 continues in the same fashion with more of the world's most famous contributing recipes. Thomas Keller and Daniel Boulud are just two of the famous names you'll find here. The photography of both the food and the environment is world class and both books have a strong emphasis on the issues raised by over fishing. All recipes in the book focus on sustainable choices.

With Christmas just round the corner and many people wondering what to buy for friends and family, this book is an ideal choice. A beautiful coffee table book for those who like browsing amazing food and waterway pictures, and a world class cook book for those who prefer to spend their time in the kitchen. And while having this award winning book to enjoy in whatever way you see fit, every time you pick it up, you'll know that others too are benefiting from your purchase or gift.

Reading Kevin Snook's brief introduction in the book and his story at greater length on the Foundation website, one can't help but be moved to sympathy and compassion for a parent to lose a son in such a fashion. It leaves us to count our blessings and hope that we should never have to experience the same. We're also moved by Kevin's courage to pursue this project despite the fact it must constantly evoke memories of his own family's suffering. It leaves us more than happy to support his efforts; we hope you will too.

a boy after the sea 2 is now available in bookshops priced at £35. It can also be ordered through The Foundation website by clicking here.

Amazon as always carry everything and more (click here). And if you don't own the original a boy after the sea, that of course is still available through all the above links.

At the end of the introduction to the first book, Kevin says that, 'if we can help and support just one troubled youngster through the difficult times that my son could not cope with, then we have succeeded'. We're sure they'll be able to do that and more. A stunning book, a great Christmas present and a truly worthy cause.

Beyond the book, http://www.dansnooktrustfoundation.com also carries details of how you can become more involved with The Foundation if you would like to do more.

With Christmas just round the corner and many people wondering what to buy for friends and family, this book is an ideal choice. A beautiful coffee table book for those who like browsing amazing food and waterway pictures, and a world class cook book for those who prefer to spend their time in the kitchen. And while having this award winning book to enjoy in whatever way you see fit, every time you pick it up, you'll know that others too are benefiting from your purchase or gift.

Reading Kevin Snook's brief introduction in the book and his story at greater length on the Foundation website, one can't help but be moved to sympathy and compassion for a parent to lose a son in such a fashion. It leaves us to count our blessings and hope that we should never have to experience the same. We're also moved by Kevin's courage to pursue this project despite the fact it must constantly evoke memories of his own family's suffering. It leaves us more than happy to support his efforts; we hope you will too.

a boy after the sea 2 is now available in bookshops priced at £35. It can also be ordered through The Foundation website by clicking here.

Amazon as always carry everything and more (click here). And if you don't own the original a boy after the sea, that of course is still available through all the above links.

At the end of the introduction to the first book, Kevin says that, 'if we can help and support just one troubled youngster through the difficult times that my son could not cope with, then we have succeeded'. We're sure they'll be able to do that and more. A stunning book, a great Christmas present and a truly worthy cause.

Beyond the book, http://www.dansnooktrustfoundation.com also carries details of how you can become more involved with The Foundation if you would like to do more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed