It was only a short time ago that we associated the grand auction houses exclusively with the artwork of old masters (and matching price tags) and would have been incredulous had we been told that we could source good wine there cheaper than Majestic. The reality is you can, but it's worth knowing a few things about how wine auctions operate before you take part, just so you get the best out of the event.

Our usual auction house of choice is Sotheby's on New Bond Street though most will follow a similar format. What's more, you don't even have to be present to bid, you can do it by telephone or even live on-line, and with a monthly event, there's always another auction just round the corner if you lose out on lots or are on holiday and miss it.

Before we consider the mechanism of how to buy, it is worth considering two questions: why buy at auction and who exactly are the sellers?

There are two reasons for buying at auction. First, through careful buying you can get things cheaper, it's a simple as that, and second, you can get some rare and/or wine with a decent bottle age. We often find that in shops, even with good wine retailers, there's few vintages available for sale before 2003/04 so if you like wine with a bit of bottle age, auctions are a good place to buy.

As for sellers, they tend to be high net worth wine collectors (Andrew Lloyd Webber recently sold a large part of his collection at auction) as well as sales from the estates of the deceased when the offspring prefer assets that are even more liquid than wine. There's a certain reliance of the auction house to check the provenance of items they sell and while one or two mistakes have been made and publicised in the past, the big name auction houses do have reputations to maintain and offer as much protection as you reasonably expect from any wine retailer.

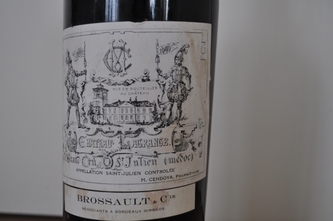

So, armed with the desire to take part, the first thing to do is see what they're selling and to know what you want. At Sotheby's, it is largely Bordeaux, red and white Burgundy and some champagne and Port. There's some Spanish, some Italian and a few cases of new world wines but here at least, it is predominantly old world with a bias to France. Most wine is also sold by the case so the usual lot size is a case of 12 bottles. Some lots are 6 bottles while in a few instances, they will sell individual bottles so pay attention to what you're buying. There's also a range of prices from £100 a case, up to (in a few instances) £50,000 a case for rare vintage top Burgundy with any one auction offering the full spectrum.

To find out what's on sale, you can look at a catalogue on line (which can be downloaded as a pdf) or walk through the door of their Bond Street premises and buy a glossy colour catalogue for £10 which is also handy for making notes in on prices etc.

Our usual auction house of choice is Sotheby's on New Bond Street though most will follow a similar format. What's more, you don't even have to be present to bid, you can do it by telephone or even live on-line, and with a monthly event, there's always another auction just round the corner if you lose out on lots or are on holiday and miss it.

Before we consider the mechanism of how to buy, it is worth considering two questions: why buy at auction and who exactly are the sellers?

There are two reasons for buying at auction. First, through careful buying you can get things cheaper, it's a simple as that, and second, you can get some rare and/or wine with a decent bottle age. We often find that in shops, even with good wine retailers, there's few vintages available for sale before 2003/04 so if you like wine with a bit of bottle age, auctions are a good place to buy.

As for sellers, they tend to be high net worth wine collectors (Andrew Lloyd Webber recently sold a large part of his collection at auction) as well as sales from the estates of the deceased when the offspring prefer assets that are even more liquid than wine. There's a certain reliance of the auction house to check the provenance of items they sell and while one or two mistakes have been made and publicised in the past, the big name auction houses do have reputations to maintain and offer as much protection as you reasonably expect from any wine retailer.

So, armed with the desire to take part, the first thing to do is see what they're selling and to know what you want. At Sotheby's, it is largely Bordeaux, red and white Burgundy and some champagne and Port. There's some Spanish, some Italian and a few cases of new world wines but here at least, it is predominantly old world with a bias to France. Most wine is also sold by the case so the usual lot size is a case of 12 bottles. Some lots are 6 bottles while in a few instances, they will sell individual bottles so pay attention to what you're buying. There's also a range of prices from £100 a case, up to (in a few instances) £50,000 a case for rare vintage top Burgundy with any one auction offering the full spectrum.

To find out what's on sale, you can look at a catalogue on line (which can be downloaded as a pdf) or walk through the door of their Bond Street premises and buy a glossy colour catalogue for £10 which is also handy for making notes in on prices etc.

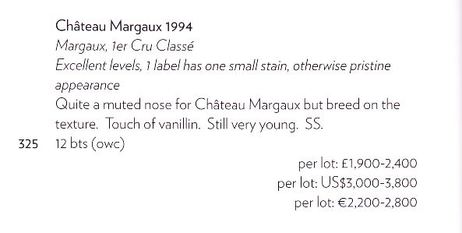

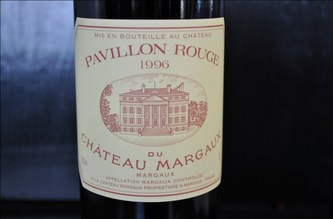

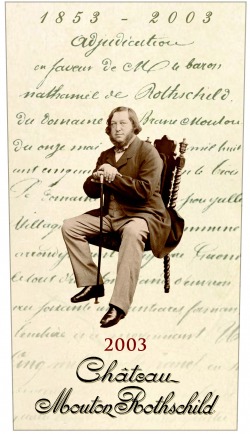

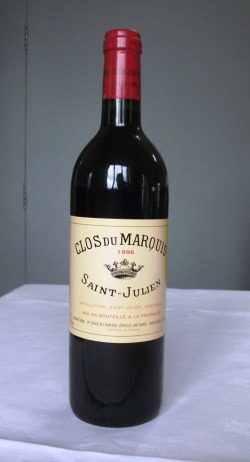

So what will the catalogue tell you? We show a sample lot to the right from today's auction - lot 325. First, obviously the name of the wine and the vintage, here, Chateau Margaux 1994. We can also see that the lot is for 12 bottles (bts), worth checking for both quantity and type for they also sell magnum formats and more. The (owc) means original wooden case suggesting this case has been stored intact since bottling.

There's also a description of the wine's appearance: excellent levels means high fill levels with wine well into the neck of the bottle, one label has a small stain but otherwise the bottles are of pristine appearance. This is important because low fill levels might mean the wine has evaporated or leaked, and damaged labels might suggest the wine has had a rough life, clearly not the case here. There has also been some tasting notes added and signed SS - Serena Sutcliffe MW, Head of Wine at Sotheby's.

Finally, we have the all important price. What they provide here is a range of where this lot might reasonably sell. In their own words, 'any bid between the high and the low pre-sale estimates would in our opinion offer a chance for success. However, all lots can realise prices above or below pre-sale estimates'. Through the auction, the auctioneer will tell you what the current bid price is and where the next increment is, and it is this price that forms your bid. What the lot finally goes for is the 'hammer price' and this is the price that forms the basis for what comes next.

This is where things get a little tricky because the price you bid is not the price you pay (sorry). You'll need to think about the buyer's premium and taxation and this is the most complex part of the transaction; let's consider both. The buyers premium is simple, this is a commission paid to the auction house on sale. At Sotheby's, it runs at 15% and therefore if you buy a case of wine for £500, you need to add on £75 commission. Next you have taxes which generally means alcohol duty and VAT. Which needs to be applied? It depends on what has already been levied during the wine's lifetime. Wine can be stored 'in bond' with no tax paid on them - duty is currently £20.25 a case. VAT tends to be the painful part because that could add more than 20% to the hammer price. There are three scenarios:

There's also a description of the wine's appearance: excellent levels means high fill levels with wine well into the neck of the bottle, one label has a small stain but otherwise the bottles are of pristine appearance. This is important because low fill levels might mean the wine has evaporated or leaked, and damaged labels might suggest the wine has had a rough life, clearly not the case here. There has also been some tasting notes added and signed SS - Serena Sutcliffe MW, Head of Wine at Sotheby's.

Finally, we have the all important price. What they provide here is a range of where this lot might reasonably sell. In their own words, 'any bid between the high and the low pre-sale estimates would in our opinion offer a chance for success. However, all lots can realise prices above or below pre-sale estimates'. Through the auction, the auctioneer will tell you what the current bid price is and where the next increment is, and it is this price that forms your bid. What the lot finally goes for is the 'hammer price' and this is the price that forms the basis for what comes next.

This is where things get a little tricky because the price you bid is not the price you pay (sorry). You'll need to think about the buyer's premium and taxation and this is the most complex part of the transaction; let's consider both. The buyers premium is simple, this is a commission paid to the auction house on sale. At Sotheby's, it runs at 15% and therefore if you buy a case of wine for £500, you need to add on £75 commission. Next you have taxes which generally means alcohol duty and VAT. Which needs to be applied? It depends on what has already been levied during the wine's lifetime. Wine can be stored 'in bond' with no tax paid on them - duty is currently £20.25 a case. VAT tends to be the painful part because that could add more than 20% to the hammer price. There are three scenarios:

- 'In bond' means no taxes will have been paid so you will need to add duty and VAT to the hammer price and buyers premium

- 'Duty paid but VAT on hammer' means that you will need to add VAT to the hammer price and buyers premium

- 'Offered duty paid' means VAT on buyer's premium only

The buyer's premium is 15% of £1,900 which is £285, and VAT on the buyer's premium is 20% of that so £57. The total cost is therefore £2,242 or £187 a bottle. So did you get a bargain?

To compare, I use wine-searcher. Putting Margaux 1994 into wine-searcher tells me that the cheapest vendor in the UK on their database retails Margaux 1994 at £237 before VAT and £285 after VAT. In other words, if you bought the wine at auction for the minimum bid price, you have saved £100 a bottle, or a stunning £1,200 on a case! For those that like percentages, it's a 34% discount. What's more, wine-searcher shows other places charging up to £350 a bottle so revealing even bigger savings.

What if you won at the top end of the bid, £2,400 a case? Now you're paying £2,976 a case or £248 a bottle, in other words, you're paying a price at the level of the keenest retail price.

This demonstrates the bargains to be had. So what should your wine buying strategy be? First, decide what you want from the catalogue. Second, see what the best retail price is for the wine. Third, knowing what tax is due, work backwards to translate the best retail price into a 'hammer price'; I use an excel spreadsheet to do the sums for me and then I make a note of this in the catalogue. Then it's simple, simply decide what price, up to the this you are prepared to pay. I usually look for at least a 10% discount to make it worthwhile (if I really want the wine) or a 30% discount if I'm more ambivalent.

Three things though are worth remembering. First, discipline is important. If you go over the 'keenest retail hammer price' you haven't got a bargain and would be better off buying it on-line. Second, be prepared to lose. There's often over 800 lots, so 800 cases of wine on sale per auction, something of what you fancy will be available at a bargain and you should be prepared to walk away from that which is not. Third, even if you end up with nothing by the end of the auction, there's another auction next month, and another the month after. Be patient and know that those that did win the lots overpaid. Who knows what bargains the next auction will bring. Don't get carried away and don't buy for the sake of it.

And that's it! Almost. While clearly I can't cover every point in this one blog post, hopefully this will be enough to show the value available at auctions and how to extract that value. With that said, next month, please don't bid against me and drive prices higher. Enjoy!

Return to homepage

To compare, I use wine-searcher. Putting Margaux 1994 into wine-searcher tells me that the cheapest vendor in the UK on their database retails Margaux 1994 at £237 before VAT and £285 after VAT. In other words, if you bought the wine at auction for the minimum bid price, you have saved £100 a bottle, or a stunning £1,200 on a case! For those that like percentages, it's a 34% discount. What's more, wine-searcher shows other places charging up to £350 a bottle so revealing even bigger savings.

What if you won at the top end of the bid, £2,400 a case? Now you're paying £2,976 a case or £248 a bottle, in other words, you're paying a price at the level of the keenest retail price.

This demonstrates the bargains to be had. So what should your wine buying strategy be? First, decide what you want from the catalogue. Second, see what the best retail price is for the wine. Third, knowing what tax is due, work backwards to translate the best retail price into a 'hammer price'; I use an excel spreadsheet to do the sums for me and then I make a note of this in the catalogue. Then it's simple, simply decide what price, up to the this you are prepared to pay. I usually look for at least a 10% discount to make it worthwhile (if I really want the wine) or a 30% discount if I'm more ambivalent.

Three things though are worth remembering. First, discipline is important. If you go over the 'keenest retail hammer price' you haven't got a bargain and would be better off buying it on-line. Second, be prepared to lose. There's often over 800 lots, so 800 cases of wine on sale per auction, something of what you fancy will be available at a bargain and you should be prepared to walk away from that which is not. Third, even if you end up with nothing by the end of the auction, there's another auction next month, and another the month after. Be patient and know that those that did win the lots overpaid. Who knows what bargains the next auction will bring. Don't get carried away and don't buy for the sake of it.

And that's it! Almost. While clearly I can't cover every point in this one blog post, hopefully this will be enough to show the value available at auctions and how to extract that value. With that said, next month, please don't bid against me and drive prices higher. Enjoy!

Return to homepage

RSS Feed

RSS Feed