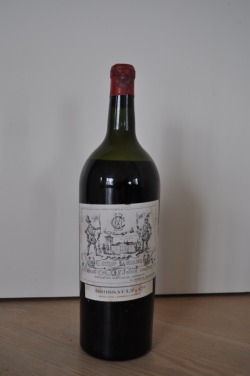

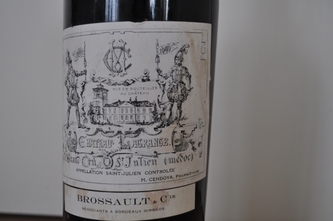

Wine is often an adventure in time travel and we recently acquired a magnum of 1949 Chateau Lagrange, a vintage that pre-dates both of us by a wide margin and brought a new order of romance to the mystical ceremony that is the opening a grand bottle. While a new breed of disgruntled wine hacks like Malcolm Gluck demand that even your Mouton be equipped with a screw top, the ever entertaining Cambridge philosopher and errant wine buff Roger Scruton in his book 'I drink therefore I am' notes:

To the naive observer the cork is there to keep the wine in the bottle and the air out of it, with the result that a small - actually a very small - proportion of vintage wines are 'corked', meaning spoiled by a defective stopper. To such an observer, the screw cap is the answer. I would respectfully retort that the risk of corking is essential to the ritual. Drinking precious wine is preceded by an elaborate process of preparation, which has much in common with the ablutions that preceded ancient religious sacrifices. The bottle is retrieved from some secret place where the gods have guarded it; it is brought reverentially to the table, dusted off and uncorked with a slow and graceful movement while the guests watch in awed silence. The sudden 'pop' that then occurs is like a sacramental bell, marking a great division in the scheme of things, between a still life bottle, and the same still life with wine.

1949 is certainly the oldest-furthest we've travelled back thus far and is considered one of the three great post war vintages (1945 and 1947 being the other two). It was also the year that George Orwell published 'Nineteen Eighty-Four' while more obliquely, clothes rationing ended in Britain.

As for Lagrange itself (Bordeaux of course), we had the St Julien variety (for there is also a Lagrange within Pomerol) with the chateau classified as a third growth in the 1855 classifications. Parker, who now rates Lagrange as second growth quality, nevertheless says that 'prior to 1983, Lagrange has suffered numerous blows to its reputation as a result of a pathetic track record of quality in the sixties and seventies'. Fortunately we can dismiss such youthful pretenders (the wines that is, not Parker) but with Parker's ratings for Lagrange going back no further than 1961, we're sailing blind but in the spirit of adventure, we little care.

How though should we approach such a wine? One hears of old wines 'collapsing' within minutes of the bottle being opened and decanting seems a no-no. A friend though pointed out a Wine Reader article by French wine collector Francois Audouze where he describes the 'slow oxygenation method' for very old wine. Under this method, one opens the wine four to five hours before the intended drinking time and checks whether it is alive (in which case an inert stopper is placed in the bottle and left till drinking time) or if the wine is feared dead, in which case the cork remains out in the hope that 'slow oxygenation' will bring it back to life.

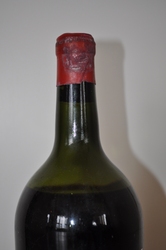

This therefore would be our plan and the countdown began. I must confess that I was a little nervous since the fill level in the bottle was middle-low shoulder. That said, as Sotheby's point out in their wine catalogues, top shoulder is the 'usual level for wines over 15 years old' so while I would like a higher fill, at 61 years old I can broadly accept that it might reasonably be at this level without undue concern.

As I use the corkscrew knife to cut through the capsule, the first observation is that the bottle is filthy around the cork top though this again is not unduly worrying since I've experienced enough bottles even 30 years old in this condition where the wine has been just perfect - after all, if you didn't wash for 61 years, it wouldn't make you a bad person, just a dirty-smelly one right? There is worse to come though, and try not to squirm here, but on closer examination there are near on microscopic creatures partying on top of the cork. This is surely not a good sign.

To the naive observer the cork is there to keep the wine in the bottle and the air out of it, with the result that a small - actually a very small - proportion of vintage wines are 'corked', meaning spoiled by a defective stopper. To such an observer, the screw cap is the answer. I would respectfully retort that the risk of corking is essential to the ritual. Drinking precious wine is preceded by an elaborate process of preparation, which has much in common with the ablutions that preceded ancient religious sacrifices. The bottle is retrieved from some secret place where the gods have guarded it; it is brought reverentially to the table, dusted off and uncorked with a slow and graceful movement while the guests watch in awed silence. The sudden 'pop' that then occurs is like a sacramental bell, marking a great division in the scheme of things, between a still life bottle, and the same still life with wine.

1949 is certainly the oldest-furthest we've travelled back thus far and is considered one of the three great post war vintages (1945 and 1947 being the other two). It was also the year that George Orwell published 'Nineteen Eighty-Four' while more obliquely, clothes rationing ended in Britain.

As for Lagrange itself (Bordeaux of course), we had the St Julien variety (for there is also a Lagrange within Pomerol) with the chateau classified as a third growth in the 1855 classifications. Parker, who now rates Lagrange as second growth quality, nevertheless says that 'prior to 1983, Lagrange has suffered numerous blows to its reputation as a result of a pathetic track record of quality in the sixties and seventies'. Fortunately we can dismiss such youthful pretenders (the wines that is, not Parker) but with Parker's ratings for Lagrange going back no further than 1961, we're sailing blind but in the spirit of adventure, we little care.

How though should we approach such a wine? One hears of old wines 'collapsing' within minutes of the bottle being opened and decanting seems a no-no. A friend though pointed out a Wine Reader article by French wine collector Francois Audouze where he describes the 'slow oxygenation method' for very old wine. Under this method, one opens the wine four to five hours before the intended drinking time and checks whether it is alive (in which case an inert stopper is placed in the bottle and left till drinking time) or if the wine is feared dead, in which case the cork remains out in the hope that 'slow oxygenation' will bring it back to life.

As I use the corkscrew knife to cut through the capsule, the first observation is that the bottle is filthy around the cork top though this again is not unduly worrying since I've experienced enough bottles even 30 years old in this condition where the wine has been just perfect - after all, if you didn't wash for 61 years, it wouldn't make you a bad person, just a dirty-smelly one right? There is worse to come though, and try not to squirm here, but on closer examination there are near on microscopic creatures partying on top of the cork. This is surely not a good sign.

Wiping over the top of the cork to scrub off the worst of the dirt, I attempt to push the cork screw tip into the top of the cork but this being rock hard, the corkscrew makes no impression but rather pushes the cork deeper into the neck of the bottle. I then try every trick I know (which admittedly is not many) to get the tip of the corkscrew into the already dislodged cork so I can avoid pushing this dirt ridden cork completely into the bottle but all to no avail. Facing up to the inevitable, I know the cork is going in and now need a back up plan.

While the aforementioned Francois Audouze will walk hot coals rather than decant, there are never hot coals around when you need them and here, decanting was now the only option. Using an old trick I vaguely remember once hearing about, I take a couple of coffee filters from the kitchen and place one in the open top of the decanter and pour. The wine dribbles through nicely to the decanter below while the filter is visibly coated in muck giving us much relief that that's not now in our glass.

Three very dirty filters later but with the dregs still in the bottom of the magnum, the wine does look attractively pale in the decanter with a nice red brick rim. For the first time I feel a pang of hope - always a portent of disaster. I stick my nose to the decanter and while there is little aroma, there was not the 'wet cardboard' smell of a corked wine. Hope rises further; fool.

By now I want to believe and go get a tasting glass. Pouring a small drop into the bottom, I undertake an obligatory swirl, a sniff and then raise the glass to my lips to go 'face to face' with the wine as Scrutton would have it. It's not corked but it's not right either. Someone once said that the story of wine is a journey of a grape from fruit juice to vinegar with something magical called wine in between. Sadly, most of the magic had now gone from this bottle and while there was a modest front note of fruit, this was rapidly overcome by the acidity of the vinegar that this wine had now mostly become.

My spirits of course sank but I'm not defeated yet. Francois has more to say on the matter,

even if a wine stinks awfully, the probability that the wine comes back to life without any bad aspect is largely greater than what one thinks. I have saved wines that people wanted to throw away. Just because oxygen is able to cure many many wounds. And if the stinking signs show that the wine is dead, why would we kill the wine now ? We have time until the dinner to see if a miracle happens. And many miracles happen.

Maybe five hours of oxygenation will provide the miracle I'm looking for. Sadly, it was not to be, no weeping madonnas, no water to wine and for that matter, no vinegar to wine; this was not to be a day of miracles. I knew we were taking a chance buying the wine in the first place and as Michael Broadbent recently commented of the 1949 vintage, 'the best are still superb but living precariously; storage and provenance are vital'. Hoping for the best but anticipating the worst, earlier that day I had already pulled two bottles of Pichon Lalande 1990 from the Eurocave so all was not lost and an embarrassment of dry glasses was avoided.

Nevertheless, it was a shame in our first (but assuredly not last) time travelling adventure to the world of the 1940s that we encountered such disappontment. While bought from a reputable supplier, I don't know how the first 61 years of this wine's life were but I'm guessing somewhere along the way it was perhaps all too much for it, the low shoulder hinted as much. That said, when we're 61, I don't think that we're going to be 'all that' either given the gastronomic life we're leading, so who am I to quibble?

But I'm not upset we tried. In life generally, when you have the objects, the car, the flat screen TV and the other toys, what's left is experience and while enjoying an unblemished Lagrange '49 would have been an experience indeed, the anticipation, the ritual and the sorrowful sink pour that followed was without doubt an appropriately worthy experience in itself. Undeterred therefore, our next real time travelling adventure will be from the greatest of the post war vintages, a 1945 Talbot in a half bottle format. We look forward to reporting back.

While the aforementioned Francois Audouze will walk hot coals rather than decant, there are never hot coals around when you need them and here, decanting was now the only option. Using an old trick I vaguely remember once hearing about, I take a couple of coffee filters from the kitchen and place one in the open top of the decanter and pour. The wine dribbles through nicely to the decanter below while the filter is visibly coated in muck giving us much relief that that's not now in our glass.

Three very dirty filters later but with the dregs still in the bottom of the magnum, the wine does look attractively pale in the decanter with a nice red brick rim. For the first time I feel a pang of hope - always a portent of disaster. I stick my nose to the decanter and while there is little aroma, there was not the 'wet cardboard' smell of a corked wine. Hope rises further; fool.

By now I want to believe and go get a tasting glass. Pouring a small drop into the bottom, I undertake an obligatory swirl, a sniff and then raise the glass to my lips to go 'face to face' with the wine as Scrutton would have it. It's not corked but it's not right either. Someone once said that the story of wine is a journey of a grape from fruit juice to vinegar with something magical called wine in between. Sadly, most of the magic had now gone from this bottle and while there was a modest front note of fruit, this was rapidly overcome by the acidity of the vinegar that this wine had now mostly become.

My spirits of course sank but I'm not defeated yet. Francois has more to say on the matter,

even if a wine stinks awfully, the probability that the wine comes back to life without any bad aspect is largely greater than what one thinks. I have saved wines that people wanted to throw away. Just because oxygen is able to cure many many wounds. And if the stinking signs show that the wine is dead, why would we kill the wine now ? We have time until the dinner to see if a miracle happens. And many miracles happen.

Maybe five hours of oxygenation will provide the miracle I'm looking for. Sadly, it was not to be, no weeping madonnas, no water to wine and for that matter, no vinegar to wine; this was not to be a day of miracles. I knew we were taking a chance buying the wine in the first place and as Michael Broadbent recently commented of the 1949 vintage, 'the best are still superb but living precariously; storage and provenance are vital'. Hoping for the best but anticipating the worst, earlier that day I had already pulled two bottles of Pichon Lalande 1990 from the Eurocave so all was not lost and an embarrassment of dry glasses was avoided.

Nevertheless, it was a shame in our first (but assuredly not last) time travelling adventure to the world of the 1940s that we encountered such disappontment. While bought from a reputable supplier, I don't know how the first 61 years of this wine's life were but I'm guessing somewhere along the way it was perhaps all too much for it, the low shoulder hinted as much. That said, when we're 61, I don't think that we're going to be 'all that' either given the gastronomic life we're leading, so who am I to quibble?

But I'm not upset we tried. In life generally, when you have the objects, the car, the flat screen TV and the other toys, what's left is experience and while enjoying an unblemished Lagrange '49 would have been an experience indeed, the anticipation, the ritual and the sorrowful sink pour that followed was without doubt an appropriately worthy experience in itself. Undeterred therefore, our next real time travelling adventure will be from the greatest of the post war vintages, a 1945 Talbot in a half bottle format. We look forward to reporting back.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed